It's week 274 and we are thinking about how hard decisions get pushed down ...

It’s week 272 of our new reality and we are thinking about what goes vira...

It is week 270 of our new reality and we are thinking about how we talk abo...

I’m excited to share a win out of the Aloha State that is an important st...

It is week 268 in our new reality and we are thinking about how we follow t...

It's week 266 in our new reality and we are thinking about what the most re...

Perhaps I am dating myself as I often do, but when I was a kid, “do-overs...

It is week 264 of our new reality and we are thinking about math.Once ...

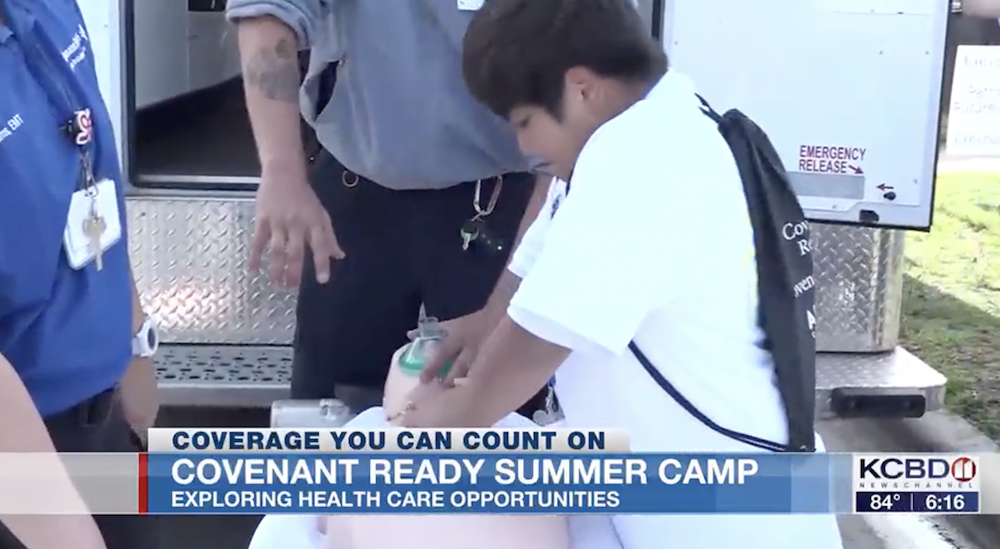

Imagine a world where high school students don’t just dream about their f...

In the Silver State a child’s education is often determined by their zip ...

In this episode, Alexis Menocal Harrigan and Alan Gottlieb welcome Nicholas...

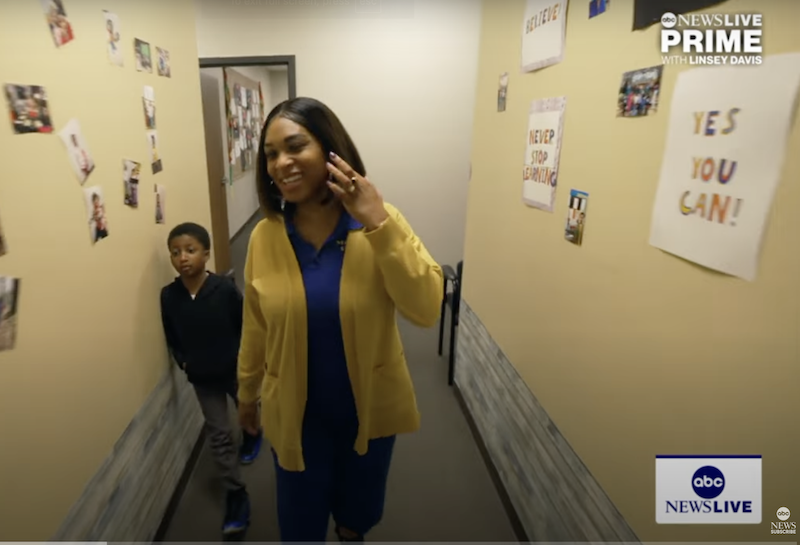

“The passage of HB 340 is an important step toward keeping our students f...